Iran’s Natural Gas: A Gateway to US-Iran Cooperation

Reported by HPMM Group according to Atlantic council ; The broad economic sanctions that go back into effect against Iran on November 5 will not significantly impact Iran’s limited natural gas exports. Iran’s export potential could emerge as a gateway to cooperation under an appropriate US strategy.

Multinational negotiations have focused on ways to increase oil production to compensate for Iranian oil lost to sanctions. However, more attention should be focused on natural gas. The global demand for natural gas is increasing, a shortage is looming, and Iran owns the second largest proved natural gas reserves in the world—totaling 33.2 trillion cubic meters or approximately a 17.2 percent share. Renewed economic sanctions will significantly hinder Iran’s ability to attract foreign investment necessary to monetize its vast reserves. However, some of Iran’s natural gas trading partners may not be compelled to cease imports, at least for the time being.

This article will review Iran’s natural gas sector and discuss strategic concerns associated with sanctions on Iranian natural gas.

The Obama and Trump administrations’ doctrines differ with regard to Iran, and continued oscillatory policy will lack the consistency that allies and partners need for their commitments. Ultimately, US policymakers must pursue a long-term strategy that preserves US interests and promotes energy security for allies and partners through a hybrid approach which also deliberately invests in Iranian youth.

In 2017, Iran produced 223.9 billion cubic meters (bcm) of natural gas, making it the third largest global producer with 6.1 percent share of the world’s natural gas market after the United States and Russia. Iran’s production primarily satisfies subsidized domestic demand. Last year, Iran’s domestic consumption totaled 214.4 bcm. Historically, Iran’s production has grown in tandem with consumption, limiting Iran’s ability to export any sizeable volume. The reopening of Iran’s economy under the terms of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) allowed it to plan and implement growth.

Iran’s 2016 – ۲۰۲۲ economic development plan prescribed ambitious natural gas production growth with the assumption of unimpeded foreign investment and growing domestic demand. Iran hoped to increase its natural gas production to 1.2 – ۱٫۳ bcm per day, or 438 – ۴۷۴ bcm per year, by 2022, double 2016 numbers. The Gas Exporting Countries Forum (GECF) forecastsIran’s domestic consumption to rise over the next two decades, albeit at a gradually slower rate as a result of improved efficiency, reaching 308 bcm per year by 2040. Based on projected growth in an unconstrained open market, Iran could have between 205 – ۲۴۱ bcm by 2022 available for export to the global market, which would then be limited by market demand and its export infrastructure.

Natural gas accounts for 70 percent of Iran’s energy mix for electricity generation, while oil contributes to 22 percent of the overall mix, and this is not likely to change. Given the size of Iran’s domestic market, domestic demand will continue to drive modest growth. For Iran to achieve robust growth, it must garner foreign investments in production projects and exportation infrastructure. Therefore, Iran’s ability to increase production and exports beyond historical trends will be directly dependent on improving relations with the United States or mustering substantial support from international partners in defiance of sanctions.

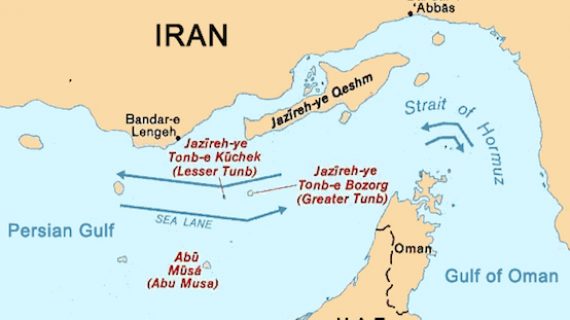

As of August 2018, Iran had the capacity to export 46.4 bcm a year through pipelines to regional partners, though it has only exported a fraction of that due to limited surplus volumes and no liquefied natural gas (LNG) capabilities. The pipeline to Turkey currently has 13 bcm capacity, to Iraq 9.1 bcm, to Azerbaijan 10 bcm, and to Armenia 2.3 bcm. Turkmenistan is historically an exporter to Iran at a maximum capacity of 12 bcm per year but this pipeline affords additional capacity. Current development projects could increase Iran’s natural gas export capacity to 119.7 bcm, to include two LNG terminals that could export beyond regional markets.

China’s search for energy and India’s desire for a competitive edge over Pakistan will inevitably play an increasing role in how the Iranian natural gas sector will perform under sanctions. Revival of the stalled Iran-Pakistan-India (IPI) pipeline project and completion of a pipeline from Iran to Oman for natural gas exports to India are two key projects that may allow Iran to increase exports.

China sees the IPI pipeline as a way to satisfy its rising domestic demand. Chinese investments into Pakistan’s natural gas infrastructure and Gwadar port have exceeded $45 billion, prompting India to develop Iran’s Chabahar Port to facilitate its maritime trading, circumventing its rival, Pakistan. As of June 2018, Pakistan and Iran have revived negotiations regarding the IPI project. Iran and India’s energy trading does not appear to be ceasing in November and both aim to complete a pipeline from Iran to Oman for future natural gas exports despite the threat of resumed sanctions. These projects could afford Iran a major outlet to the Far Eastern market but will require substantial geopolitical commitments and financial investments in defiance of US sanctions.

Russia’s current stranglehold on Europe’s natural gas market causes substantial anxiety due to Russia’s political leverage over dependent countries, particularly in the European Union (In 2015, seven EU countries and five non–EU countries were 100 percent dependent on Russia for natural gas imports.) Beyond the demand for natural gas, Europe’s interests are threatened with emerging US secondary sanctions. France’s Total has already pulled out of business ventures, and many other European companies are reconsidering the risk of doing business with Iran. In 2017, EU trade with Iran amounted to approximately $25 billion. The EU seeks to shield European companies through reviving a twenty-year-old statute known as the “blocking regulation.” The EU is also devising a “Special Purpose Vehicle” to facilitate European companies’ non-dollar trade with Iran. It remains to be seen how effective these efforts will be.

Iran’s inability to produce and export natural gas will deny the global energy market, including Europe, an additional source for energy security. US policymakers should pursue a strategy that best preserves US interests while promoting energy security for its allies and partners. The United States, as outlined in the National Security Strategy, seeks to promote the viability of global energy sources, not just for itself, but for allies.

However, if Iran becomes the regional hub for oil and natural gas exports, energy exports would afford Iran additional geopolitical power and economic wealth. Under current geopolitical conditions and looming sanctions, Iran cannot unilaterally monetize its vast proved natural gas reserves. Iran possesses an incredible opportunity if it can strike a balanced relationship with the United States, an approach the regime’s hardliners have vehemently opposed.

A Hybrid Approach toward Iran is Best

The United States requires an integrated regional strategy to protect its national interests, preserve favor among Iranian youth, and encourage long-term cooperation with Iran. There are three potential approaches: cooperation, confrontation, and a hybrid.

A confrontational approach has done little to change regime behavior in the past, but the United States has maintained favor with Iranian youth while denying the Iranian regime revenue to support malign activities in the region. Confronting Iran will punish those seeking an additional source for natural gas for the foreseeable future unless the United States is willing to subsidize US LNG exports to Europe and minimize Russia’s market share. A cooperative approach invites an alternative source of natural gas for the global market and may help to increase energy security, but may indirectly fund activities that counter US interests. A hybrid approach based on a strategy of containment could preserve pro-American sentiment for the next generation of policymakers to pursue cooperation and moderation. Iran’s natural gas sector can become the gateway to cooperation, exploiting Iran’s desires to become a major exporter of natural gas and using it to reward and embolden reforms in the Iranian government.

Under a hybrid approach, the United States would pursue a two-pronged strategy that promotes global energy security and maintains a dialogue with the Iranian government while managing conflict in the short term. The first supports competing natural gas projects in the region, lessening the demand for Iran’s natural gas. (In Central Asia, due to rising demand for natural gas, the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India (TAPI) pipeline will export 33 bcm of Turkmen natural gas to South Asian countries. In the Mediterranean, recent natural gas discoveries in Egypt, Israel, and Cyprus afford two opportunities: an alternative supply to Turkey and the potential emergence of Egypt as a Middle East energy hub.) Though episodes of confrontation may be necessary, long-term cooperation ought to be the end goal.

The second part, an “Iranian Natural Gas Initiative Program,” modeled on Iraq’s Oil-for-Food Program, serves as a component to the hybrid approach toward Iran. While the Oil-for-Food Program was marred by extensive corruption, we believe that with additional oversight and deliberate planning, the United States could offer this concession in good faith, to provide energy security for allies and show support for the Iranian population. The initiative targets Iranian youth, who will see the long-term benefits of international inclusion and would appropriate revenue from the monetization of Iran’s natural gas to support humanitarian needs and divert funds from supporting malign activities in the region. However, getting Iran to agree to anything less than what it had under the JCPOA, to include more oversight and international control, will be a tough task.

In most international relations scenarios, there is no straightforward right-or-wrong strategy; there are only strategies with different consequences. Unlike the last round of sanctions lifted under the terms of the JCPOA in 2015, the United States is now confronting Iran without the support of Europe, Russia or China. The world’s rapidly expanding natural gas market offers significant economic growth opportunities for Iran, if the United States and Iran could develop a more cooperative relationship. However, the United States risks affording Iran economic space to expand malign activities, while the Iranian regime risks its legitimacy by negotiating with the West and allowing the international community greater access within Iran.

Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei will not live forever, but his policies may. Short of accepting Iran as a partner to promote global energy security, monetization of natural gas will help shape Iranian youth’s perceptions of democracy and influence future Iranian leaders toward reform. To reach these goals, US policymakers should understand Iran’s potential to monetize its natural gas reserves in the next decade and pursue a strategy more likely to survive political cycles and hostilities in the short-term, with the goal of cooperation in the long-term.

Major Thang Q. Tran is an Army Special Forces Officer who is currently pursuing a Master’s Degree in Defense Analysis (Financial Management) from the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, California, while also pursuing a Master of Business Administration through Mississippi State University. He has served with the 10th Special Forces Group (Airborne) and has multiple operational deployments in support of Operation Enduring Freedom and the Resolute Support Mission in Afghanistan. The views expressed in this article are those of him and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defense of the U.S. Government.

Major Alan W. Lancaster is an Army Special Forces Officer and recent graduate of the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, California, with a Master’s Degree in Defense Analysis (Irregular Warfare). He has served with the 3rdSpecial Forces Group (Airborne) and has deployed in support of Operation Enduring Freedom and Resolute Support Mission. The view expressed in this article are those of him and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defense of the U.S. Government.